De huidepidermis, samen met zijn aanhangsels zoals zweet- en talgklieren, biedt een totaal huidoppervlak van ongeveer 25 m2 en is een van de grootste epitheeloppervlakken voor interactie met microben [1]. De huid is een barrière van de eerste lijn vanuit de externe omgeving en staat er continu mee in contact. Het gastro-intestinale (GI) kanaal is een van de grootste interfaces (30 m2) tussen de gastheer en zijn omgeving [2]. Er wordt geschat dat ongeveer 60 ton voedsel in een mensenleven door het darmkanaal gaat, wat allemaal een grote invloed heeft op de menselijke gezondheid [3]. Zowel de darm als de huid zijn sterk doordrongen van microbiota, waarbij wordt geschat dat de huid ongeveer 1012 microbiele cellen heeft, terwijl de darm goed is voor 1014 microbiele cellen [4,5]. De microbiota wijzen op de verzameling van specifieke micro-organismen die aanwezig zijn binnen een bepaalde omgeving. De opkomst van next-generation sequencing in het afgelopen decennium heeft ongekende inzichten geboden in de samenstelling van het microbioom, zowel op de huid als in de darm. Het microbioom verwijst naar de genomen aanwezig in een bepaalde omgeving, wat betekent dat het de ophoping is van al hun genetisch materiaal (d.w.z. DNA en RNA). Beide organen worden gekenmerkt door een lage microbiële diversiteit op fylum-niveau, maar een hoge diversiteit op soortniveau [6]. Het microbioom biedt de gastheer tal van voordelen, zoals het vormen van het immuunsysteem, bescherming tegen pathogenen, afbraak van metabolieten en het behoud van een gezonde barrière [3].

De immuun-modulerende potentie van het microbioom op verre orgaanlocaties is een groeiend onderzoeksgebied. Vooral de invloed van het darmmicrobioom op verre organen, zoals de longen, hersenen en huid, heeft de volgende onderzoeksgebieden gecreëerd: darm-long as, darm-hersen as en darm-huid as [7]. Het aangeboren en adaptieve immuunsysteem verandert de microbiële samenstelling; echter, het lokale microbioom kan ook het immuunsysteem moduleren. De onderliggende mechanismen van hoe het darmmicrobioom het immuunsysteem van de huid verandert, en vice versa, worden momenteel onderzocht. Verschillende huidpathologieën worden gepresenteerd als darmcomorbiditeiten. Verschillende studies hebben de tweerichtingsverbinding tussen darmdysbiose en onevenwichtigheden in de huidhomeostase aangetoond, met een specifieke rol van darmmicrobiota-dysbiose in de pathofysiologie van meerdere inflammatoire ziekten [8,9,10].

Een samenvatting van recente bevindingen in het huid- en darmmicrobioom bij meerdere huidaandoeningen staat in deze review, waarbij enkele potentiële mechanismen worden belicht die ten grondslag liggen aan de darm-huid as.

Huid versus Darm Barrière

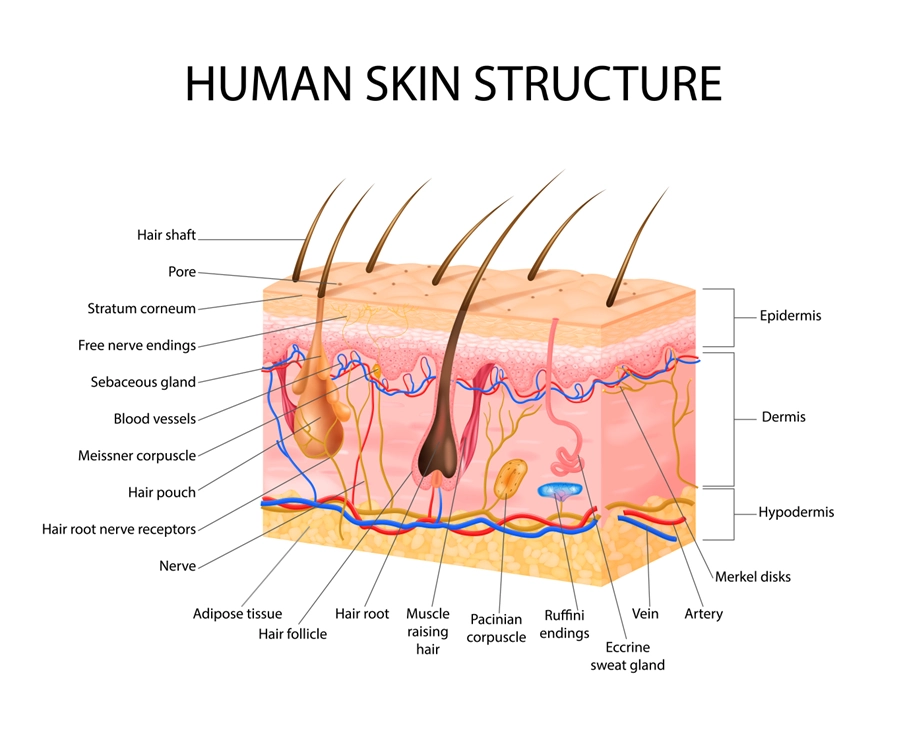

De darm- en huidbarrière delen opvallend veel kenmerken. De darm en huid zijn sterk analoog aan elkaar qua doel en functionaliteit. Beide organen zijn sterk geïnnerveerd en gevaccineerd, omdat ze beiden essentieel zijn voor immuun- en neuro-endocriene functies [11]. De darm-huid as ontstaat door deze gelijkenis [11]. Het binnenoppervlak van de darm en het buitenoppervlak van de huid worden beide bedekt door epitheelcellen (EC’s) die rechtstreeks contact hebben met de exogene omgeving [12]. Op deze manier wordt het immuunsysteem continu geprikkeld om schadelijke en gunstige stoffen te onderscheiden. De activatie van immuuncellen begint al vroeg in het leven en vormt de basis voor tolerantie, een cruciaal concept waarvan wordt verondersteld dat het defect is bij verschillende auto-immuunziekten [13]. EC’s onderhouden een belangrijke schakel tussen het interne lichaam en de externe omgeving. Ze fungeren als een eerste verdedigingslinie om de binnenkomst van micro-organismen te voorkomen [12]. Keratine, dat aanwezig is in het gestratificeerde squameuze epitheel van de huid, vormt een formidabele fysieke barrière voor de meeste micro-organismen [14]. Bovendien maakt dit bestanddeel de huid bestand tegen zwakke zuren en basen, bacteriële enzymen en toxines [15]. Slijmvliezen bieden vergelijkbare mechanische barrières, omdat het bestaat uit een glycoproteïnelaag bovenop het epitheel waar commensale bacteriën verblijven [16,17]. De epitheelmembranen produceren beschermende chemicaliën die micro-organismen elimineren [18]. De zuurgraad van de huid (pH van 5,4 tot 5,9) creëert een onherbergzame omgeving voor potentiële pathogenen en remt bacteriële groei [19]. Talg, geproduceerd door de talgklieren, fungeert als een afdichting voor haarfollikels en bevat verschillende antimicrobiële moleculen en specifieke voedingslipiden voor gunstige micro-organismen [20,21]. Ondertussen bevatten speeksel en traanvocht lysozymen, gevolgd door de maagslijmvliezen die sterke zuren en eiwitverterende enzymen afscheiden [22]. Bovendien vangt slijm micro-organismen die het spijsverterings- en ademhalingssysteem binnendringen [23].

De tweede verdedigingslinie bestaat uit antimicrobiële peptiden (AMP’s), fagocyten en aangeboren lymfoïde cellen (ILC’s) [24]. Deze twee eerste verdedigingslinies vormen het aangeboren immuunsysteem [23]. AMP’s geproduceerd door keratinocyten, zoals cathelicidin en psorasin, bieden een effectieve barrièrefunctie voor de huid [25,26]. De serineprotease Kallikrein 5 (KLK5) splijt cathelicidin in actieve peptiden, zoals LL-37 [27]. Vergeleken met de huid varieert de samenstelling van de intestinale epitheelbarrière gedurende het maagdarmkanaal. Het proximale deel van het maagdarmkanaal, de mond en de slokdarm, is analoog aan de huid, bedekt met meerdere lagen van squameus epitheel, dat wordt gereinigd door slijm van speekselklieren en andere klieren [28]. Het overgebleven deel van het spijsverteringskanaal omvat een enkele laag actieve cellen, bijv. slijmbekercellen (slijmsecretie), enterochromaffinecellen (hormoonsecretie), enterocyten of colonocyten (absorptie), etc. [29,30]. Het intestinale epitheel bestaat uit een enkele laag enterocyten of colonocyten, en de integriteit van de barrière wordt beschermd door het immuunsysteem. De absorberende functionaliteit van de enterocyten in de dunne darm leidt tot een onderbroken laag slijm met minder slijmbekercellen [31]. Paneth-cellen zijn verrijkt in de crypten van de dunne darm die AMP’s afscheiden, die in de complexe slijmlaag worden geïntegreerd [32].

Microbiële geassocieerde moleculaire patronen (MAMP’s) worden bemonsterd via antigeenopname door membranen (M) cellen en slijmbekercellen naar dendritische cellen (DC’s), samen met directe transepitheliale lumen DC’s. Microbiële signalen worden waargenomen door ROR𝛾t aangeboren lymfoïde C-cellen (groep 3 ILC’s) die interleukine-17 (IL-17) en IL-22 produceren [33]. De laatste werkt rechtstreeks op de intestinale epitheelcellen (IEC’s) en activeert schadeherstelmechanismen, AMP’s en mucinegenen [34]. Plasmacellen in Peyer’s patches, gestimuleerd door DC’s, produceren IgA in het lamina propria op een T-cel-onafhankelijke manier [35,36]. De dikke darm daarentegen bevat een dikke, continue slijmlaag om de microbiota te compartimenteren, waarbij IgA en AMP’s een secundaire rol spelen [17]. De controle van immunologische processen binnen slijmvliezen is afhankelijk van de interactie tussen EC’s en DC’s, aangezien beide celtypen betrokken zijn bij het waarnemen en bemonsteren van antigenen [12]. Zowel in de huid als in de darm worden pathogenen bemonsterd via mechanismen die niet afhankelijk zijn van M-cellen [37]. De enige DC’s die binnen de epidermis worden gevonden, zijn de Langerhans-cellen (LC’s) [12].

Andere overeenkomsten tussen de darm en huidweefsels zijn de hoge celvernieuwingsgraad, wat hechting en infectie door de koloniserende microbiota remt [38,39]. De huid en de darm zijn de twee belangrijkste niches die prokaryotische en eukaryotische symbiotische micro-organismen herbergen [40,41]. Echter, de residente microbiota zijn vaak betrokken en spelen een cruciale rol bij de pathogenese van verschillende ziekten [42]. Beide weefsels reageren sterk op stress en angst, omdat ze vergelijkbare uitdagingen tegenkomen.

Opmerkelijk genoeg omvatten ziekten zoals inflammatoire darmziekte (IBD) en psoriasis een disfunctie van de epitheelbarrière en een verhoogde omzettingsgraad van epitheelcellen. De verhoogde permeabiliteit van de epidermale huid en de intestinale barrière komt door de versterkte interactie van allergenen en pathogenen met ontstekingsreceptoren van immuuncellen. Beide ziekten hebben een vergelijkbare immuunrespons en betrekken fagocyten, dendritische en natuurlijke killercellen, samen met een reeks cytokinen en AMP’s die een T-celrespons induceren [43]. Bovendien worden beide ziekten gekenmerkt door dysbiose in de samenstelling van het microbiële ecosysteem dat de respectieve interfaceranden bedekt [43].

Het darmmicrobioom is het grootste endocriene orgaan en produceert minstens 30 hormoonachtige verbindingen, zoals korteketenvetzuren (SCFA’s), secundaire galzuren, cortisol en neurotransmitters zoals gamma-aminoboterzuur (GABA), serotonine, dopamine en tryptofaan. Bepaalde leden van het darmmicrobioom reageren op hormonen die door de gastheer worden uitgescheiden [44]. De hormoonachtige pleiotropische verbindingen die door het darmmicrobioom worden geproduceerd, komen in de bloedbaan terecht en kunnen op afgelegen organen en systemen werken, zoals de huid [44]. Talrijke studies hebben bewijs geleverd voor een diepgaande tweezijdige relatie tussen gastro-intestinale gezondheid en huidhomeostase door aanpassing van het immuunsysteem [45,46,47]. Modulatie van het immuunsysteem vindt voornamelijk plaats via het darmmicrobioom. Echter, commensale huidmicrobiota zijn even essentieel voor het behoud van de immuunhomeostase van de huid [48]. Zowel de darm als de huid herbergen diverse bacteriële, schimmel- en virale soorten die symbiose met de menselijke omgeving behouden. Het verstoren van deze balans kan leiden tot een verminderde barrièrefunctie. Het herstel van de huidhomeostase na verstoring of stress via het darmmicrobioom heeft invloed op zowel aangeboren als adaptieve immuniteit.

Betrokkenheid van de huid- en darmmicrobiomen

De huid is de grootste en meest externe barrière van het lichaam met de buitenomgeving. Het is rijk aan immuuncellen en zwaar gekoloniseerd door microbieel leven, dat op zijn beurt de immuuncellen traint en het welzijn van de gastheer bepaalt [49]. Het huidmicrobioom heeft de afgelopen jaren aanzienlijke aandacht gekregen in de dermatologie, huidaandoeningen en de verbinding en invloed op het immuunsysteem. Veel huidaandoeningen worden geassocieerd met een onevenwicht in het huidmicrobioom (Tabel 1). Steeds meer studies tonen verrijkte pathogenen en microbiota die geassocieerd worden met huidaandoeningen, sommige zijn voor de hand liggend en andere verrassender. Het is echter moeilijk vast te stellen of het veranderde huidmicrobioom een oorzaak of gevolg is van de huidaandoening.”

Hieronder bieden we een overzicht van negen veelvoorkomende huidaandoeningen en hun respectievelijke pathofysiologie, en de kennis over de verstoringen in hun huidmicrobioom, een verstoord darmmicrobioom, en/of de relatie met een specifiek dieet.

Acne Vulgaris (Acne): Acne Vulgaris is een complexe aandoening waarbij verschillende factoren samenkomen om het te veroorzaken. De balans van de huidmicrobiota, hormonale schommelingen, talgproductie, dieetinvloeden en immuunpaden spelen allen een belangrijke rol bij het ontstaan van deze aandoening.

De huidmicrobiota speelt een cruciale rol in de pathologie van Acne Vulgaris, vooral bepaalde stammen van Cutibacterium acnes. De verstoring in de huidmicrobiota is geassocieerd met diverse factoren, zoals de inductie van talg, directe stimulatie van het immuunsysteem, diversiteit binnen de C. acnes populatie, porfyrineproductie, mobiele genetische elementen, CRISPR/CAS loci en de productie van korteketenvetzuren (SCFAs). Ondanks uitgebreid onderzoek blijft de precieze choreografie van deze pathogene gebeurtenissen enigszins ongrijpbaar.

Interessant genoeg laten studies duidelijke verschillen zien in de huidmicrobiota van acne patiënten, met een lagere aanwezigheid van gunstige bacteriën en een toename van bepaalde bacteriestammen die met de aandoening geassocieerd worden. Deze disbalans beperkt zich niet tot de huid; onderzoek wijst op veranderingen in de diversiteit van de darmmicrobiota bij acne patiënten, wat duidt op een mogelijk verband tussen darmgezondheid en de ontwikkeling of ernst van acne.

De relatie tussen acne en dieet benadrukt verder de complexiteit van deze aandoening. Diëten met een hoge glycemische lading, verzadigde vetten en specifieke vetzuurinname worden geassocieerd met de ernst van acne. Deze voedingscomponenten verstoren mogelijk signaalpaden voor voedingsstoffen, wat leidt tot ongecontroleerde stimulatie van bepaalde biologische processen zoals de synthese van vetzuren en triglyceriden in talg. Deze veranderingen kunnen een omgeving bevorderen die gunstig is voor de groei van Cutibacterium acnes, waardoor acne-symptomen verergeren.

Therapeutische benaderingen omvatten voornamelijk antibacteriële middelen, retinoïden of comedolytische agentia. De multifactoriële aard van acne vereist echter een begrip dat de onderliggende ziekteprocessen meerdere bijdragende factoren omvatten. Gepersonaliseerde behandelingen die rekening houden met de complexe interactie tussen huidmicrobiota, hormonale balans, dieetinvloeden en immuunreacties bieden hoop op effectieve behandeling van deze aandoening.

Atopische Dermatitis (AD): Atopische Dermatitis, een ontstekingsziekte van de huid, is het resultaat van een complex samenspel tussen genetische aanleg, omgevingsfactoren en immuunreacties. De pathofysiologie omvat een verstoorde huidbarrière, chronische ontsteking en microbiële dysbiose, vooral in de huidmicrobiota.

De microbiële dysbiose van de huid bij AD vertoont veranderingen gekenmerkt door een verminderde bacteriële diversiteit en een verhoogde aanwezigheid van Staphylococcus aureus, terwijl gunstige bacteriën zoals Cutibacterium, Corynebacterium, Streptococcus, Acinetobacter, Prevotella en Malassezia afnemen. Deze disbalans heeft een significante invloed op de inflammatoire reacties die bij AD optreden, vooral door de groei en pathogenese van Staphylococcus aureus.

Bovendien is darmdysbiose bij AD-patiënten een onderwerp van aanzienlijke interesse. Studies suggereren dat patiënten met AD een verminderde diversiteit van de darmmicrobiota vertonen, met specifieke variaties in de abundantie van verschillende bacteriesoorten in vergelijking met gezonde controles. Probiotische interventies hebben belofte getoond in het beheer van AD, wat wijst op het potentieel om de darmmicrobiota te beïnvloeden om immuunreacties bij huidaandoeningen te beïnvloeden.

De correlatie tussen dieet en AD benadrukt verder de veelzijdige aard van deze aandoening. Verminderde consumptie van fruit, groenten en omega-3 vetzuren, samen met een verhoogde inname van omega-6 vetzuren, zijn geassocieerd met AD. Deze voedingsgewoonten kunnen ontstekingen bevorderen en de ernst van AD beïnvloeden, hoewel verder onderzoek vereist is om het definitieve effect van dieetmanipulaties op deze aandoening te bevestigen.

Psoriasis: Psoriasis, een immuun-gemedieerde inflammatoire aandoening, kenmerkt zich door roodheid, schilfering en verdikte huidletsels op verschillende delen van het lichaam. Deze aandoening wordt beïnvloed door genetische factoren, levensstijl en omgeving, en wordt beschouwd als een complexe ziekte met systemische gevolgen.

Het immuungemedieerde karakter van psoriasis draait voornamelijk om de Th17-route, waarbij ontstekingen worden veroorzaakt door IL-23/IL-17-gemedieerde reacties, terwijl TNF het ontstekingsproces versterkt. Hoewel er vooruitgang is geboekt in het begrijpen van de immunologische basis, blijft de exacte oorzaak van psoriasis onduidelijk. De aanwezigheid van een antivirale respons in psoriasis, gesuggereerd door de aanwezigheid van type I interferonen, wijst op mogelijke betrokkenheid van de huidmicrobiota bij virale reacties.

Studie naar de psoriatische huidmicrobiota onthult een gevarieerd beeld, met verschillende uitkomsten met betrekking tot microbiële diversiteit en soortenrijkdom. De huid van psoriasispatiënten vertoont vaak een veranderde bacteriële samenstelling, met een hogere aanwezigheid van Staphylococcus- en Streptococcus-soorten en een verminderde diversiteit in bepaalde microbiële groepen. Daarnaast is darmdysbiose in verband gebracht met psoriasis, wat mogelijk de ernst van de aandoening beïnvloedt en de respons op behandelingen kan beïnvloeden.

De complexe relatie tussen psoriasis en darmgezondheid wordt duidelijk door de associaties met intestinale immuunstoornissen, zoals IBD, UC en coeliakie. Structurele afwijkingen in de darm en veranderingen in de darmintegriteit zijn gerapporteerd bij psoriasispatiënten, wat wijst op systemische implicaties die verder gaan dan alleen de huidverschijnselen. Behandelingen voor psoriasis, inclusief systemische therapieën, hebben invloed op de darmmicrobiota, wat wijst op potentiële interventiemogelijkheden.

Levensstijl en dieetfactoren hebben aanzienlijke invloed op psoriasis. Roken, alcoholgebruik en obesitas zijn gekoppeld aan verergering van huidletsels en respons op behandelingen. Aan de andere kant hebben gezonde eetgewoonten, inclusief gewichtsmanagement en specifieke dieetregimes zoals een caloriearm ketogeen dieet of intermitterend vasten, potentiële voordelen laten zien bij het beheren van de ernst van psoriasis.

De samenvattingen van deze aandoeningen onderstrepen de complexe wisselwerking tussen huidaandoeningen, microbiële veranderingen, immuunreacties en dieetinvloeden. Een dieper begrip van deze veelzijdige verbanden is cruciaal voor de ontwikkeling van gerichte interventies en gepersonaliseerde therapieën om deze chronische aandoeningen effectief te beheren.

Hidradenitis Suppurativa (HS): Deze chronische huidaandoening, die ongeveer 0,3% van de wereldbevolking treft, manifesteert zich op plaatsen waar de huid tegen elkaar wrijft of waar zweetklieren aanwezig zijn, zoals de oksels, liezen of onder de borsten. HS veroorzaakt pijnlijke, terugkerende bulten die kunnen openspringen en tunnels onder de huid kunnen vormen. Hoewel de exacte oorzaak onduidelijk blijft, zijn er sterke aanwijzingen voor een verband met het immuunsysteem en ontstekingsreacties. Onderzoek suggereert dat genetica, hormonale factoren en levensstijlgewoonten zoals roken en obesitas mogelijk bijdragen aan de ontwikkeling ervan.

Rosacea: Rosacea is een chronische huidaandoening gekenmerkt door roodheid, zichtbare bloedvaten en soms kleine rode bultjes op het gezicht. Hoewel de exacte oorzaak niet volledig wordt begrepen, wordt aangenomen dat het een combinatie is van genetische en omgevingsfactoren. Bepaalde triggers zoals blootstelling aan de zon, pikant voedsel, alcohol, stress en sommige huidverzorgingsproducten kunnen de symptomen verergeren. Cathelicidine, een eiwit betrokken bij de immuunafweer van het lichaam, lijkt overmatig tot expressie te komen in rosacea-gevoelige huid, wat leidt tot ontsteking en verwijding van bloedvaten. De huidmicrobiota, vooral een overgroei van bepaalde mijten en bacteriën, kan ook bijdragen aan de ontwikkeling en verergering ervan.

Roos en Seborroïsch Eczeem: Roos, een veelvoorkomende hoofdhuidaandoening gekenmerkt door schilfering en jeuk, wordt vaak geassocieerd met de aanwezigheid van een schimmel genaamd Malassezia. Deze gistachtige schimmel is een normaal onderdeel van de hoofdhuidmicrobiota, maar een overgroei ervan kan leiden tot irritatie en schilfering. Seborroïsch eczeem is een ernstigere vorm van roos die gepaard gaat met rode, ontstoken huid en zich kan uitbreiden buiten de hoofdhuid naar andere gebieden met talgklieren, zoals het gezicht en bovenlichaam. Beide aandoeningen kunnen verband houden met onevenwichtigheden in de microbiële gemeenschap van de huid, vooral een toename van bepaalde schimmel- of bacteriesoorten. Dieet en gezondheid van de darmen lijken ook een rol te spelen, waarbij enig bewijs een verband legt tussen suikerinname en darmgerelateerde problemen en de ernst van de symptomen.

Alopecia: Alopecia areata veroorzaakt plotseling haarverlies in kleine, ronde plekken op de hoofdhuid of andere delen van het lichaam. Het wordt beschouwd als een auto-immuunziekte waarbij het immuunsysteem van het lichaam per ongeluk de haarzakjes aanvalt, waardoor ze krimpen en stoppen met haargroei. Hoewel genetica en disfunctie van het immuunsysteem als belangrijke factoren worden beschouwd, blijven de exacte triggers voor deze immuunrespons onduidelijk. Onderzoek onderzoekt de rol van de huidmicrobiota bij deze aandoening, waarbij wordt vermoed dat een onevenwicht in bepaalde micro-organismen op de hoofdhuid zou kunnen bijdragen aan het ontstaan of de progressie ervan. Bovendien suggereert enig bewijs dat de gezondheid van de darmen en de samenstelling van de darmmicrobiota van invloed kunnen zijn op de ontwikkeling of ernst van alopecia. Voedingsstoffentekorten, met name vitamines en mineralen die essentieel zijn voor een gezonde haargroei, spelen ook een rol, wat wijst op een potentieel verband tussen dieet en het beheer van alopecia.

Huidkanker

Huidkanker is een veelvoorkomende maligniteit die kan worden onderverdeeld in twee categorieën: invasieve melanoom, waarbij melanocyten ongecontroleerd delen, en niet-melanoom huidkankers (NMSC’s). De laatste omvat tumoren met een keratinocytaire oorsprong, zoals basaalcelcarcinoom (BCC) en plaveiselcelcarcinoom (SCC) [299]. Er zijn verschillende risicofactoren die kunnen leiden tot melanoom en NMSC’s, waaronder constitutionele aanleg, immuunsuppressieve status en blootstelling aan omgevingsrisicofactoren zoals ultraviolette straling [300]. Bovendien kunnen actinische keratose en Bowen’s ziekte ook leiden tot SCC [301]. De immunologie met betrekking tot cutane componenten werd de afgelopen decennia beter begrepen door mechanismen van immuunbewaking en het immunoediting raamwerk. De immunogeniteit van tumorcellen verandert door een gewijzigde expressie van (tumor-geassocieerde) antigenen, zoals verminderde MHC-1-expressie, wat resulteert in de ontwikkeling van maligniteit [302].

De impact van virussen en UV-straling op huidkanker is uitgebreid onderzocht. Onlangs werd een lagere incidentie van huidkanker ontdekt bij kiemvrije ratten. Hierdoor wordt vermoed dat een verstoorde huidmicrobiota kan leiden tot de ontwikkeling van verschillende vormen van huidkanker. Het is echter nog onduidelijk of tumorcellen of microbiële dysbiose de progressie veroorzaken [303]. Onderzoeken hebben de link onderzocht tussen verschillende vormen van huidkanker en dysbiose van het bacteriële huidmicrobioom bij ontstekingsziekten waarbij Th17 betrokken is, zoals psoriasis en acne [103]. Bovendien zijn SCC en actinische keratose onlangs ook geassocieerd met een toename van bepaalde stammen van S. aureus in combinatie met een afname van huidcommensalen [100]. Verder vertoonden melanoommonsters volgens een recent onderzoek door Mrázek et al. verhoogde niveaus van Fusobacterium- en Trueperella-genera [102]. Bovendien kan een toename van Merkelcel polyomavirus (MCPyV), een virus dat naar verluidt een aanhoudende bewoner van de huid is, leiden tot Merkelcelcarcinoom (MCC) [103]. Aan de andere kant bleek uit onderzoek dat specifieke S. epidermidis-stammen selectief de proliferatie van tumorcellijnen remmen en bescherming bieden tegen de voortgang van door UVB geïnduceerde huidpapillomen in preklinische modellen [304].

Patiënten met kanker worden vaak blootgesteld aan een verstoord darmmicrobioom als gevolg van therapieën die de samenstelling en immuniteit van deze microbiota beïnvloeden [306]. Hoewel de relatie tussen deze dysbiose en huidkanker specifiek nog onduidelijk is, is de relatie met kanker in het algemeen al enigszins onderzocht. Meer onderzoek is echter nodig om de correlatie tussen darmdysbiose en huidkanker te onderzoeken. Ten slotte is het onzeker of tumorontwikkeling secundair is aan bacteriële dysbiose.

Wondgenezing

Wondgenezing van de huid is een zeer complex en georganiseerd proces en bestaat uit overlappende fasen van acute genezing [307]. Meerdere celtypen, voornamelijk epidermale keratinocyten, neutrofielen en macrofagen, zijn betrokken en interageren met de aanwezige commensale microbiota. Wanneer een van deze fasen wordt belemmerd, zal de epitheliale barrière niet goed genezen en wordt een wond chronisch. Verstoorde wondgenezing is een grote uitdaging voor het gezondheidszorgsysteem en treft ongeveer 1% tot 2% van de bevolking in ontwikkelde landen [308,309]. De prevalentie van chronische wonden is hoger bij oudere mensen met onderliggende pathologieën zoals diabetes mellitus, vaatziekten en obesitas [310].

Wonden bieden een ideale omgeving voor microbiota om toegang te krijgen tot onderliggend weefsel en om te koloniseren en te groeien [318,319]. Commensale microbiota zijn naar verluidt gunstig voor het wondgenezingsproces. Ze zijn essentieel voor het reguleren van het huidinnate immuunsysteem en stimuleren de productie van antimicrobiële moleculen die bescherming bieden tegen intracellulaire pathogenen [318,320,321].

Veranderingen in het commensale huidmicrobioom kunnen bijdragen aan de vorming van chronische wonden. Recent onderzoek bij diermodellen suggereert dat probiotica niet-genezende wonden kunnen hinderen en genezen. Dit vormt een boeiend onderzoeksveld met veelbelovende toepassingen voor therapieën en cosmetica. Het begrijpen van de interacties tussen het microbioom en de gastheerweefsels zal leiden tot een beter begrip van gezondheid en ziekte en zal nieuwe mogelijkheden creëren. Er is behoefte aan goed ontworpen klinische onderzoeken om de effectiviteit van op microbiota gerichte behandelingen te beoordelen.

Conclusies

De huidaandoeningen zoals besproken in dit manuscript zijn het resultaat van een complexe interactie tussen genetische aanleg, levensstijl en het immuunsysteem. Meer specifiek staat dit laatste constant in verbinding met het zenuwstelsel en het endocriene systeem. Deze interacties stellen microbiota in staat een sleutelrol te spelen, vooral in organen zoals de huid en darmen die rijk zijn aan immunoregulatoren en microbiota. Bovendien suggereren observaties zoals de preventie van AD door probiotica en de verhoogde prevalentie van darmgerelateerde aandoeningen bij chronische huidaandoeningen dat huidaandoeningen kunnen worden gelinkt aan het maagdarmstelsel. De belangrijkste hypothese is gebaseerd op de gezondheid van de darm, die wordt gereguleerd door voedingsfactoren, gemedieerd via het darmmicrobioom en het immuunsysteem, wat leidt tot systemische effecten, inclusief huidgezondheid. De integriteit van de darmbarrière speelt hierbij een sleutelrol, maar het bestaan ervan blijft sterk bediscussieerd.

Deze dysbiose van het darmmicrobioom vormt een interessant onderzoeksgebied met toepassingsmogelijkheden. Pre- en probiotica gericht op het darmmicrobioom kunnen worden gebruikt om de huidgezondheid te beïnvloeden [45]. Muizen die probiotica kregen met Lactobacillus reuteri vertoonden bijvoorbeeld een glanzendere en dikkere vacht, gemedieerd door IL-10, en verbeterden ook het integumentaire systeem toen gezuiverde Foxp3+ T-cellen werden toegevoegd [329]. In een placebogecontroleerd onderzoek verkregen gezonde vrijwilligers een lagere transepidermale waterverlies en een lagere huidgevoeligheid bij consumptie van probiotica in vergelijking met de placebogroep [330]. Interessant genoeg hebben specifieke diëten, zoals caloriebeperking en vetarme diëten, ook verbeteringen in de darmepitheelbarrière of huidconditie laten zien, waaronder acne vulgaris, AD, psoriasis, wondgenezing, huidkanker en zelfs veroudering van de huid [339,340].

De aantrekkelijkheid van gerichte interventies op het darmmicrobioom via orale toediening lijkt omgekeerd evenredig te zijn met de complexiteit van het richten van de darm-huidas: het reguleren van het darmmicrobioom kan leiden tot systemische effecten, inclusief de huid en andere organen. Goed ontworpen klinische onderzoeken zijn nodig om de effectiviteit van op microbiota gerichte behandelingen te beoordelen. Recentelijk ontwikkelde sequencingtechnologieën zouden een gedetailleerd begrip van de mediators van het darm- en huidmicrobioom mogelijk moeten maken. Deze technologieën moeten worden ondersteund door biomarkeranalyses (zoals IgA, calprotectine en immuunmetingen) om de interactie tussen het microbioom en de integriteit van de darmbarrière te identificeren.

Hoewel het microbioom ook virale microbiota omvat, is er weinig bewijs beschikbaar over hoe virussen huidaandoeningen en de darmgezondheid beïnvloeden. Het aankomende volledige genoomonderzoek zou ons begrip van de rol van virussen in de darm-huidas moeten vergemakkelijken.

Huidgezondheidsresultaten moeten worden gedefinieerd om de impact te bepalen. Huidtapestrippen, dat recentelijk werd geïntroduceerd voor eiwit- en mRNA-kwantificatie, maakt niet-invasieve bemonstering mogelijk die minder belastend is voor de proefpersonen. Echter, huidtapestrippen onthult slechts beperkte informatie in vergelijking met huidbiopsieën.

Ten slotte moeten onderzoeksprotocollen deze complexiteit in overweging nemen: de kwaliteit van het vastleggen van voedingsgewoonten is cruciaal en is afhankelijk van de gekozen methode, zoals patiëntgerapporteerde uitkomstmaten (bijv. een voedselfrequentievragenlijst versus digitale apps voor calorieën tellen en voedingsdatabases). Bovendien moet het tijdstip van bemonstering zorgvuldig worden overwogen: proefpersonen kunnen bijvoorbeeld gevast zijn op het moment van bemonstering door het overslaan van ontbijt, in tegenstelling tot degenen die dat niet hebben gedaan. Bovendien moet rekening worden gehouden met de impact van het circadiane ritme in toekomstige klinische onderzoeken. De huidige literatuur ontbeert studies die de impact van het circadiane ritme van voedingsopname beschrijven. Het onderzoek van Parkar et al. beoordeelde het bewijs dat de effecten van veranderde slaap- en eetpatronen aantoont, die het gastheercircadiaansysteem kunnen verstoren en het darmmicrobioom kunnen beïnvloeden [341]. Naast ons eigen circadiane ritme, blijkt dat het microbioom ook een interne klok heeft die wordt gereguleerd door microbële metabolieten. Bepaalde voedingsstoffen worden vermoedelijk beter gemetaboliseerd op bepaalde momenten van de dag. Een hoge calorie-inname tijdens de avonduren wordt bijvoorbeeld geassocieerd met gewichtstoename, terwijl dezelfde calorie-inname tijdens de ochtenduren resulteert in gewichtsbehoud [345].

Kortom, de darm-huidas, met een centrale rol voor onze microbiota, vormt een boeiend onderzoeksgebied met veelbelovende therapeutische en cosmetische toepassingen. Het ontrafelen van de interacties tussen het microbioom en de gastheerweefsels zal leiden tot een beter begrip van gezondheid en ziekte en zal nieuwe mogelijkheden creëren. De noodzaak van goed ontworpen onderzoeken is van primair belang en vereist multidisciplinaire teams om samen te werken, in lijn met de samenwerking tussen ons eigen lichaam en microbiota.